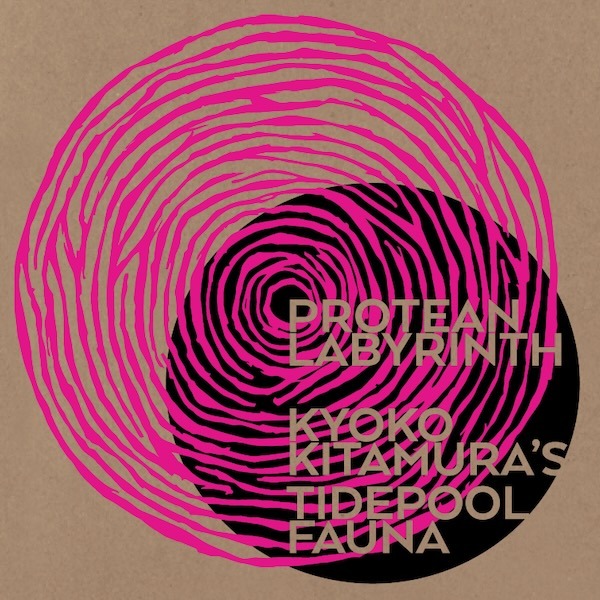

Bridging the Gap

“Bridging the Gap” is Kitamura’s new project concept conceived in 2024. Kitamura has always been interested in ways to bring people of diverse backgrounds and generations together, the main reason she has continued to pursue wordless vocal music – because language, while being an important tool to communicate, can also exclude. Taking this a step…